Continuous Insulation

A Solution for Performance and Aesthetics

Whether managing extreme thermal challenges, meeting escalating codes and acoustic requirements, CI integrates both performance and aesthetics to commercial enclosures. By Angie ogino

If you want to fully appreciate an insulating material’s capabilities, it is helpful to consider its performance in both everyday applications and extreme situations. Whether delivering thermal comfort in an arctic climate zone, meeting the most rigorous of code requirements for government buildings or supporting the design details of an urban-chic, open joint assembly, the choice of continuous insulation can influence occupant comfort, energy efficiency and even a building’s design aesthetic.

Lyle Axelarris PE is a building enclosure consultant with Design Alaska, one of the state’s largest design firms, and a Building Science instructor at the Boston Architectural College and the University of Washington. Residing in Alaska’s extreme climate for 20 years before moving to relatively balmy Michigan, Axelarris has witnessed shifts in how building professionals think about CI as a tool to mitigate thermal bridging, protect against condensation inside the wall assembly and, more recently, contribute to emerging design trends.

Let’s begin by defining continuous insulation. Continuous insulation is a practice defined by ASHRAE 90.1— Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings as “insulation that is continuous across all structural members without thermal bridges other than fasteners and service openings. It is installed on the interior or exterior or is integral to any opaque surface of the opening.” As this approach significantly reduces uninsulated wall space and the opportunity for heat to move from the inside to the cooler exterior, it helps reduce thermal bridging.

Considering Codes, Comfort and Efficiency

Whether an enclosure is designed as a commercial, healthcare or residential structure, an insulating material’s ability to deliver thermal comfort and support energy efficiency is essential. While ASHRAE 90.1 and the IECC codes have continued to increase insulation levels, requirements are even higher for federal buildings. Explaining that construction built to the United Facility Criteria has to be 30 percent better than ASHRAE 90.1, Axelarris says the standard has required Design Alaska to incorporate as much as 6 to 9 inches of CI into designs.

It’s somewhat surprising that Alaska’s building codes have not adopted CI as a requirement. For non-federal projects in the 49th state, Axelarris notes that the practice of specifying CI is largely a matter of practicality rather than compliance.

“Energy is expensive; there are a high number of heating degree days and comfort is imperative,” he says. “If you don’t make your building more airtight and properly insulate it, it will get damaged more quickly and it will be uncomfortable for occupants.”

Managing moisture is an ongoing challenge as well. Installed as CI in a rainscreen assembly, mineral wool delivers a vapor-permeable and non-absorbent mechanism for allowing air to ventilate the assembly. Insulation helps limit condensation forming by preventing warm, moist air from reaching a dew point and allowing condensation to form.

“The industry is coming to a critical tipping point when it comes to understanding how the choice of insulation can help an assembly stay dry and keep occupants comfortable,” says Axelarris. “The type of insulation you use can have an incredible impact on the actual moisture performance of the assembly.”

As open façade designs become more popular, architects do not have to choose between thermal performance and the urban chic aesthetic.

Solving for Design and Contracting Concerns

Continuous insulation helps manage challenges well beyond the Alaska climate. In the lower 48 states, façade trends and critical performance criteria are informing the evolution of CI as a design element behind the façade. Exterior designs featuring open joint assemblies where dramatic gaps and offsets can add visual intrigue, also present challenges when it comes to visible components behind the façade.

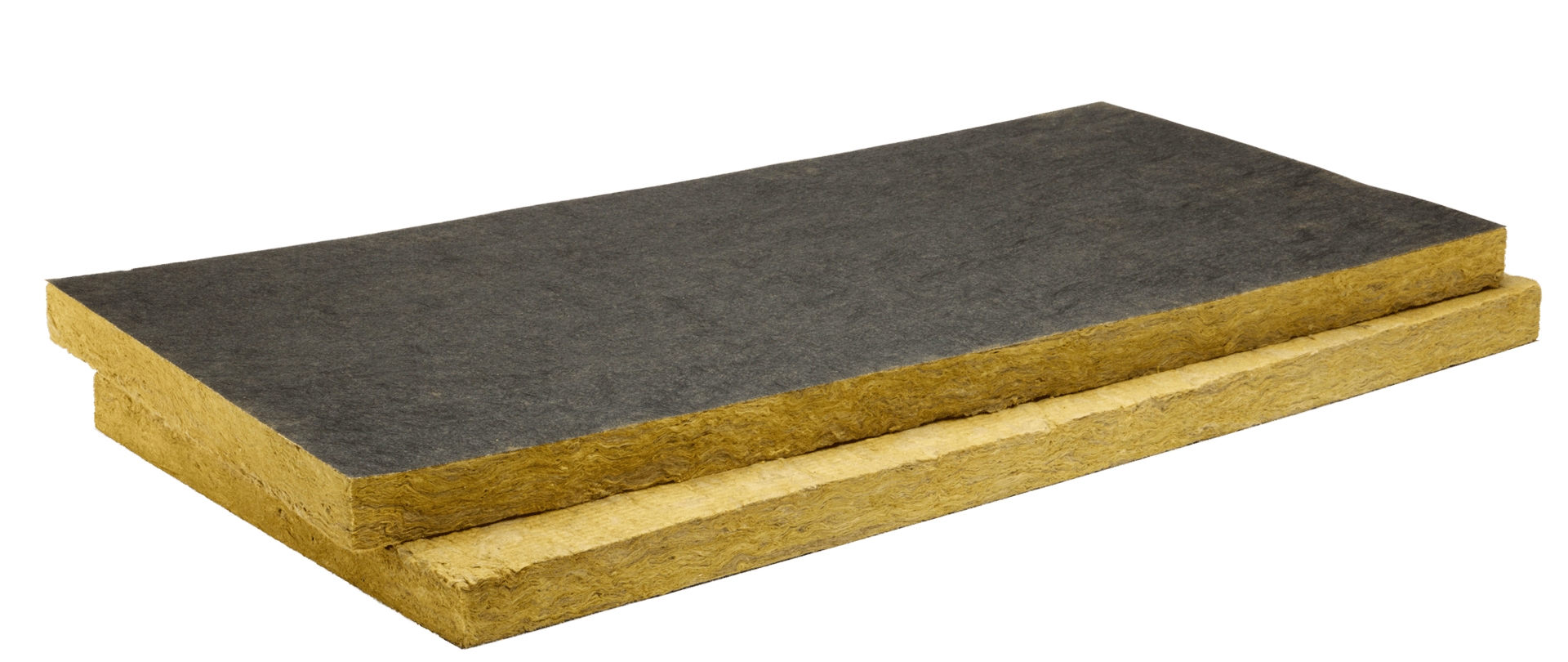

One option is to coat or cover materials behind the façade so that they don’t disrupt from the aesthetic. However, new innovations in mineral wool insulation allow this component to subtly blend into the background. As the façade will always be the focus of a building’s exterior, consideration should be given to any element that might disrupt the aesthetic.

Continuous insulation has presented a design dilemma in the past when the material was visible in rainscreen applications or open-joint designs. To solve for this design detail, some manufacturers developed a mineral wool insulation with a black facing that provides the same benefits as legacy CI, while adding camouflage or contouring aspects to the design. A rain barrier equipped with a bonded black facing offers flexibility of design for designers, as well as ease of installation for contractors. This new option’s facing is made of fiberglass that is factory-applied to the insulation. This combination has been designed to stay in place and maintain integrity during and following installation.

An air barrier should not be installed on the outside of the exterior insulation but instead tied to the wall of sheathing. Properly installed, it is the exterior insulation that may be visible in the façade, thus the introduction of a dark option.

Labor and time on the jobsite are other factors to consider. The architect is always going to want to keep elements dark behind the façade but the additional steps to achieve this add time and labor.

“We have received pushback from contractors to simplify the building envelope system. As each additional step is added, there is another labor-intensive pass around the building,” Axelarris says. Installing a factory-applied faced mineral wool CI can help contractors avoid the extra step of having to apply a membrane or dark coating to conceal elements behind the façade.

Beyond supporting energy efficiency and thermal performance, continuous insulation behind the façade can serve a range of purposes. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s expansion integrated continuous mineral wool insulation into the building’s open-joint façade. This insulation was specified to provide energy-saving CI with critical fire-resistive characteristics. Axelarris notes that NFPA testing requirements helped expand the use of mineral wool semi-rigid insulation for its non-combustibility but that moisture management is another important performance attribute mineral wool offers in the enclosure.

He says the industry’s awareness of the types of semi-rigid mineral wool CI has changed over the past 10 to 15 years.

“We have finally reached a critical mass when it comes to the industry understanding the need for assemblies to dry out and how the vapor permeance of insulation affects an assembly’s response to becoming wet,” he says.

Whether managing extreme thermal challenges, meeting escalating codes and acoustic requirements, managing moisture in the assembly or supporting emerging design practices, semi-rigid mineral wool CI integrates both performance and aesthetics to commercial enclosures.

Images courtesy of Owens Corning.

Angie Ogino is Thermafiber/Owens Corning’s Technical Services Leader. She has more than 20 years’ experience in the mineral wool and firestopping industry, providing engineering judgments and technical assistance on mineral wool product performance for architects, building officials and contractors in fire, sound, and thermal applications.