The

Right Material

for Any Climate

The wall you install will need to be able to stand up to various climate challenges, so how do you choose materials that guarantee high performance?

By Micah Garrett

Building codes are continuing to adapt to changing environments and grow stronger based on an increasing knowledge of building science. Design pursuits such as Net Zero, LEED certification, and Passivhaus are no longer fringe movements but standards to pursue, and continue to gain greater adoption and traction in the marketplace. These trends lead many builders to ask, “What changes do I need to make to my standard construction practices? What materials or wall assemblies should I be researching and learning how to build with?”

To answer these questions, it is important to understand how a wall assembly performs in specific climates. Not every climate zone requires the same set of standards or materials. However, there are several simple guidelines that apply in most cases. An exterior wall needs to protect the interior of the building from moisture, air infiltration, temperature change, sound transmission, and occasionally extreme weather events.

Climate Control

Progressive regional codes require that exterior walls must have an effective weather barrier, possess low vapor permeance, achieve varying degrees of airtightness, insulate against fluctuating outside temperatures and possess structural capacity to resist extreme weather events. These general characteristics will vary in degree and scale depending on the specific climate zone or robustness of the adopted code.

For example climate zones 6 and 7 require more insulation than in zones 3 and 4 because the average temperatures in zones 6 and 7 are lower than in zones 3 and 4. Air barriers are more commonly combined with vapor retarders in cold dry climates. Whereas in hot and humid climates cavity-framed walls often rely on just house wraps or zip board so that the building can breathe and reduce the likelihood of mold. Knowing and understanding basic climate and construction differences can reduce significant headache and property loss when building across multiple climate zones.

The average building owner only considers a few things when building or purchasing a structure: Is the building attractive; is the building comfortable to live and work in; and is the building cost effective to maintain and operate? What is not considered is that for a building to be comfortable and cost effective to operate, it needs to be optimized for the climate it is built in. Though adoption of higher standards may be slow, many are starting to ask tougher questions.

Some parts of the world are starting to push the construction industry forward. In the province of British Columbia, the BC Step Code is taking a hard look at the actual performance of building materials and requiring builders to construct progressively higher performing structures. British Columbia has set a goal that all homes should be near net zero in the next ten to twenty years. Furthermore, to ensure proper construction practices, they are requiring a blower-door pressure test to ensure a structure performs at or below specific U-values (The metric reciprocal of R-Value). This is a huge step forward and many builders are feeling the pressure to achieve this cost effectively.

Climate Challenges

While the climate across the United States is more varied in comparison to British Columbia; many of the demands placed on a structure by its environment are universal and inform the choices of building materials. Unique climate challenges exist but planning should be of utmost importance. If you are building in a high wind zone or along the coast, the choice of materials should focus on strength and durability.

Similarly, if you are building in a wildfire prone area, the focus is on fire resistant finishes and high fire ratings. If the average temperature outside of the structure is well above or below 72 degrees, then your focus is on insulation and R-value.

Builders in varying climates must overcome natural challenges while delivering performance and aesthetics in a cost-effective manner. More and more often this requires greater labor and additional materials that require specialized training. This is why many builders are taking a look at insulating concrete forms. ICFs provide answers and solutions for every climate zone while being fast to build with. Insulating concrete forms are a time-tested material that have full acceptance in North American building codes. Additionally, with the current volatility in the lumber markets ICFs are a cost-effective solution.

Strong Performance

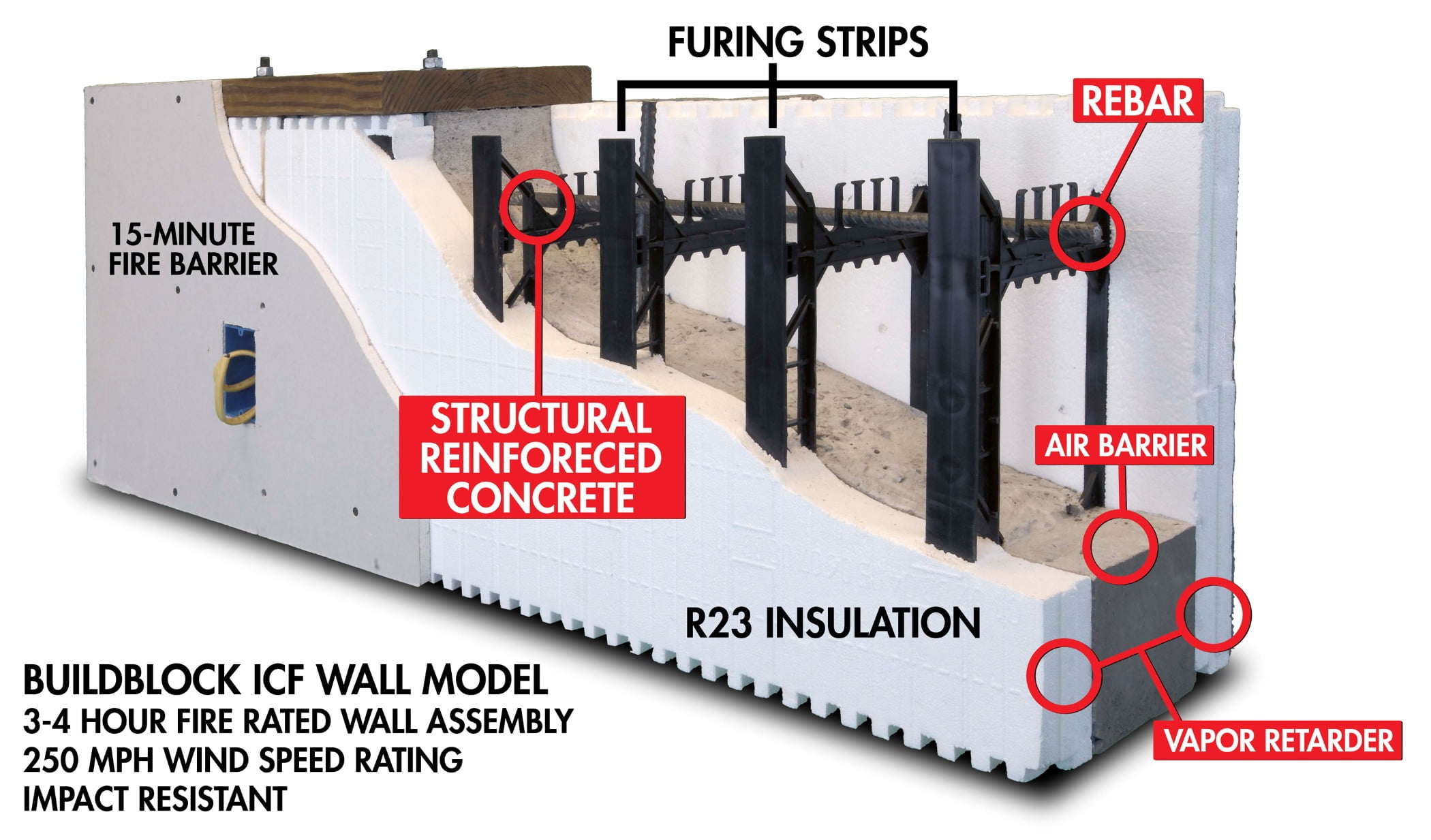

The materials used in an ICF are simple. There are two expanded polystyrene panels which are connected by insulated polypropylene webs that act as embedded furring strips and rebar ties. ICF blocks are stacked like Legos, reinforced with rebar, and filled with concrete. They stay in place, permanently creating a monolithic, structural, mass wall that is continuously insulated on both sides. These materials while simple, perform powerfully when put together.

EPS foam has long been tested for its thermal performance. On average a finished ICF wall performs at an R-23 while in steady state during a guarded hotbox test. A guarded hotbox test places an ICF wall assembly between two environments: room temperature on one side and extreme temperatures on the other. The test evaluates the time and energy required to maintain room temperature on one side of the test. During a guarded hotbox test an ICF wall takes up to six days to transition to steady state, and during that same period performs significantly better than R-23. Rarely in nature will a wall be exposed to hotbox conditions where extreme temperatures are blown at it continuously.

When tested for vapor permeance, the two EPS panels at two and half inches each provide results under one perm. Each panel qualifies as a vapor barrier. The concrete itself at an average core thickness of 6 inches creates an air barrier, and in its continuous monolithic nature forms an extremely air-tight wall. These attributes combine all the power of vapor retarders, air barriers, and weather barriers into one material.

Moisture (along with hot and cold), stays outside because air cannot infiltrate the wall. Since the wall is a mass wall, and EPS is not a medium for mold growth, humidity and moisture are not a problem for the wall itself. The hot and cold you put inside the structure to keep it comfortable stays consistent, resulting in comfortable occupants. Enter ecstatic parents who do not have to put locks on the thermostat or worry about expensive utility bills.

Choosing the Right Building Materials

Another important characteristic of building materials is their ability to help structures resist extreme weather events. With the effects of climate change, many natural disasters are becoming more extreme and regular. We have all heard our elders saying, “They just don’t build them like they used to.” The truth is we can build stronger and safer structures that can resist what Mother Nature throws at them. ICFs use concrete, a time-tested material that provides lasting results. ICF safe rooms built to FEMA standards are rated up to 250 mph wind speeds. Fundamentally, those same designs can be applied to a standard ICF wall.

ICFs create strong structures that can resist hurricanes and tornados. ICFs also excel at fire ratings and on average deliver between 3 to 4-plus hours depending on core thickness. When designed in conjunction with other fire-resistant materials and appropriate site mitigation, an ICF structure has a good chance of surviving wildfires.

Final Thoughts

Just one more thing: A 6-inch ICF wall also performs with an STC rating between 50 to 54. This means shouting and other loud noises cannot easily be heard outside the wall. The neighbor that mows their lawn at 6 a.m. is no longer the bane of your existence. That dog that doesn’t seem to ever stop barking can now be just a distant memory. ICFs are also fast to build with, can be assembled with a small crew and used for both above and below grade structures.

ICFs are not just for residential buildings but are commonly used for commercial, industrial, and institutional buildings. Combine all these benefits into one material and you can confidently build with ICFs from California to Maine and across any climate zone, while achieving superior results. The decision is up to you. What material is right for you?

Images Courtesy of BuildBlock

Micah joined BuildBlock Building Systems in October of 2018 as its Chief Operating Officer. The son of the founder, he has gained exposure and learned about manufacturing and the ICF industry since a very young age. As COO, Garrett manages BuildBlock’s manufacturing, operations, technical, and accounting departments. He also works directly with each manufacturing facility to ensure production meets demands and helps solve any problems those facilities may encounter related to BuildBlock’s tooling and equipment.